A conversation with Mildred Beltre

2023-24 Visiting Artist Mildred Beltré talks with Artistic Director Sayward Schoonmaker, along with CEO Emily Zaengle and Stone Quarry Board Member Kim Waale, about her work and artistic practice. Below is an excerpt from their conversation.

Sayward: Please join me in welcoming Mildred Beltré. Mildred is an artist living and working in New York City. Her works in print and drawing examine facets of social change. Her current work involves using self-portrait and text-based work to explore race, social interaction, desire and the simultaneous but opposing concepts of hyper visibility and invisibility. Mildred is the co-founder of Brooklyn High-Art! Machine, an ongoing, socially engaged collaborative art project in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, that addresses gentrification and community building through art making. Mildred and her collaborator Oasa DuVerney are currently artists-in-residence of the Met Civic Practice Partnership. Launched in 2017, this two-year artist residency program is for socially engaged artists and artist collectives. Mildred is also a 2023 recipient of a NYSCA Individual Artist Grant.

How did you first come to printmaking and which materials do you return to again and again in your practice?

Mildred: That’s a great question. But before I tackle that, I want to thank you, Sayward and Emily, for inviting me to the park.

When I went to college, I was somewhat recruited by an art teacher to take classes, and he happened to be the printmaker. His name is Fred Hagstrom, and I am eternally grateful to him for many reasons. I took lots of art classes, but printmaking was the one that kind of took. It matched the way I think: There's an indirectness, a time lag, in the way printmaking works. That lag helps me think. There’s also something in the labor of printmaking. The first printmaking process I engaged deeply in was stone lithography. There are so many steps to it. You grind the stone in several passes with different grits, honing and honing. The surface is amazing. It's hard work, but also meditative. Labor can sometimes be meditative for me. I would work hard to prepare a surface, make the drawing quickly, and then slow down again to print. It felt like casting magic spells and pouring potions over the stone. It was this ritual over the stone that hooked me. From lithography, I moved onto others processes like etching. At the University of Iowa, where I did my graduate work, we made our own ink, which was so cool and another laborious process. You had to mull the ink before you printed, and before printing there were steps to soak the paper. Super nerdy printmaking stuff! It suited me at the time. I don't make lithographs anymore because I think they're tedious and unrewarding.

Sayward: You mentioned that you would make the drawing fast on the stone. It’s a choice with flair, to labor and then make the mark quickly.

Mildred: Yes, it was a lot of preparation and then I’d improvise, then go back to the labor. When you do all of that to the stone, the mark feels like it has to be very important. I incorporated a lot of techniques: I would draw, do Xerox transfers, and I was using text back then. It was very 90s work! Identity-based and working out college-age issues. What happened over that time is still what I return to again and again in many ways: ideas about labor and actual labor. Thinking about my place in the world, humor, borrowing images, creating images. It was all there.

I have an impulse to recycle work. I loved printing lithographs, but I wasn't a super good printer and so I ended up with a lot of bad prints. I always felt obligated to do something with those because I didn’t want to waste them. I would collage over the bad prints. The idea of the remix, which is something that I've been thinking about lately, I think was present then—the idea of taking something that was finished and then doing something else over it.

Sayward: I think there's infinite possibilities in remixing because everything is always changing. You're changing, the things around you are changing. Remixing old materials makes new. Printmaking techniques involve tedious but satisfying labor, as do most textile practices. You employ textile techniques in some of your work, and you employ visual vocabularies related to textiles such as the grid and the stitch. How did textiles enter your practice?

Mildred: I think what happened was lithography is obviously something that's dependent on equipment, facilities, and institutions. I wasn't affiliated with an institution for a very long time. Right before I finished graduate school, a fellow student taught me how to make woodcuts. I loved it because I could make prints without facilities. Then there was actually a long period of time after grad school where I didn’t make much work. To me, one of the main things about printmaking is this idea of layering. You create this layered image through repeated printing. During that time after school, I was drawing, but I couldn't print, and I realized I was making drawings by gluing transparent pieces of paper on top of each other. I was so desperate to print!

The woodcuts I could make by hand. Then I took a class, learned how to silkscreen, and was working at the Lower Eastside Print Shop where I applied for a residency. I was productive there for a long time. And that's where I produced all the Chance Woodcuts.

Chance Woodcuts, Reduction woodcuts, 22in x 30in, 2002-2006

Before this time, I discovered knitting and I was knitting, knitting, knitting: sweaters and socks. I love knitting socks. I love knit socks. Knitting kind of filled the art void. I kind of didn't need to make art anymore because I was so happy knitting!

Sayward: Oh yes, I know about knitting filling the art void! What never tires about knitting, for me, is that you are creating fabric from a single strand. It’s portable, like the constraints of Animal, Vegetable, Mineral. Knitting is the same: 2 sticks, 1 string.

Mildred: What you say about the single strand makes me think how alongside most of this art making I have always been involved in political organizing. I was part of this group called Escuela Popular Norteña, which was a public education center located in New Mexico. A lot of the things that we did there had to do with creating nonhierarchical practices, really thinking about horizontality and how to live collectively. Not just think about it or talk about it or read about it, but to practice it and invite people who were organizing in different locations. Escuela was somewhat based after the Highlander School in Tennessee founded by Myles Horton. A lot of civil rights leaders would come to Highlander to talk about what was happening in each of their areas, develop strategies, and share. Escuela had a more Latino focus. I worked with them for a long time.

After a while, I realized that the shapes I was working with in my drawings, which I call “little bowls”, and the rules I applied to them, were also about social organizing, how people organize themselves relationally, or how people respond to each other relationally. If I drew something somewhere then, things had to shift in the picture plane. The metaphor I would use in my mind as I made the drawings was people in a subway car: When one person gets in, everyone has to shift and adjust. No one's really talking to each other, but they are responding. I thought about that as a communal space where people were cooperating for the most part. But then I became dissatisfied with that political metaphor because the little bowls are all still individual things.

Body and the Dream (MLK), Graphite, Walnut Ink, Watercolor, 39” x 50”, 2015

Mildred: I was thinking about interconnection, but I realized that those things weren't interconnected, they were just responding to each other. I wanted to think through ideas of actual interconnectedness, and what I landed on was crochet. In crochet you can’t undo any part of it without really affecting another part of it, and each part is built on the other part. So, the idea of the one line became important to me.

I started small, and then I started crocheting my own hair, then I wanted to make the crochet bigger and spatial. So, I cut paper into strips and crocheted the paper.

Untitled, Crocheted Paper, 2012

Mildred: This is all a long way to talk about how I got to the grid. The unit was something I was thinking about and the way the unit functioned in relationship to other units or parts of the whole which led to the crocheting, which, I think, eventually led to the grid.

Sayward: That’s amazing because I feel it’s rare for someone to begin with a tangly, organic form like crochet and then arrive at the grid.

Mildred: Well, I think it’s why I started working with string, then crocheting the paper led me to cross stitching. Cross stitch is the grid. I think that happens a lot, right? A certain material language develops, and when I switch out that material for another, it still stands in for the language. I was using wool, and then I moved to my own hair. In Where My Dream At?, it is needle felted wool but it also looks like my hair.

Sayward: I love that work.

Where My Dream At?, Linen, Wool, 16in x 9in x 3in, 2015

Mildred: I’ve talked about labor, but this work is something that happened really quickly. I just had the idea to make this, I thought it was really funny, and I made it quickly. I was super happy with it; It made me laugh.

Sayward: I have a theory about work that happens fast. I have great fondness and respect for the one-liner, which is often maligned as a quick meaningless thing. But I think good one-liners require rumination. Then, the wonderful moment of coalescence feels as if the idea graced upon you, and you make it fast. I think to notice the moment of coalescence is years in the making.

Mildred: I mean, it came from a lot of other things. The idea came after The Dream Workers series. It came after I made this video where I made my mom read the “I Have a Dream” speech. My mom's an immigrant, and I wanted her to read the speech to hear what those words sounded like coming from a black woman with a Spanish accent. What would those words mean to an immigrant, someone who came to this country in 1967, shortly after that speech was delivered? I wondered what was the relationship between the dream that Martin Luther King Jr was speaking of and the dream of immigrants coming to this country? Then I was thinking, in the present, if people were to reflect on the speech, how would they talk about it? And Where My Dream At? is what I came up with. It gets to the failure of the dream.

Sayward: The Dream Workers series is silkscreen, drawing, and collage, focusing on a civil rights workers. Each work is titled with the first name of a civil rights worker. Earlier today, I went through each one, and looked up anyone I didn’t know by first name. Here is everyone: Angela Davis, Martin Luther King, Medgar Evers, Assata Shakur, Huey Newton, Stockley Carmichael, Ella Baker, Malcolm X, Fannie Lou Hamer, Fred Hampton, Denise Oliver-Velez, Yuri Kochiyama, Richard Aoki, Bobby Seale, Katherine Cleaver, Dorothy Height.

Mildred: My mom is an immigrant, and I'm basically an immigrant in that I grew up in an immigrant community, speaking Spanish at home. I learned English in school. I was the first person born in this country, and my sisters were born in the Dominican Republic. I'm Black, I'm not African American. As I move through the world, I feel like the specifics of African Americans is part of what I deal with day to day. But it's not necessarily a history that is mine directly. It is mine now. The history of enslaved African in the Caribbean has a different timeline and character so it was incumbent upon me to educate myself. Part of the Dream Worker series was about educating myself by researching the actors of the Civil Rights Movement. It’s a wide range of people and not only the usual suspects. The Southern National Christian Congress, Ella Baker, who was important for me as someone who was studying popular education, thinking about the coalitional aspects of the Black Panthers. The Civil Rights movement was a Black movement, but it wasn't only Black people involved: there was a lot of Asian, Black-Asian solidarity. The Panthers also made a lot of alliances with poor whites. And I feel like that's history that really needs to be recovered. The allyship that was happening and the movement that they were building was truly coalitional, and I feel like it’s a segment of history that gets erased.

Sayward: I learned that the Black Panthers also supported disability rights.

Mildred: The Young Lords were the Puerto Rican response to the Black Panthers, and they did a ton of work in New York and in Chicago. This history feels more present now, but it wasn't for a long time. There are people like Claudette Colvin, who was a young woman who refused to give up her seat on the bus before Rosa Parks. But because she was a teen mom, the movement didn’t deem her respectable enough. Like I said, educating myself gives me an opportunity to research, and the reason these folks aren’t wholly visible in the series is because the work isn't done. It's an unfinished project, like a photo that's not fully developed, like the image isn't clear; it's not fully visible yet.

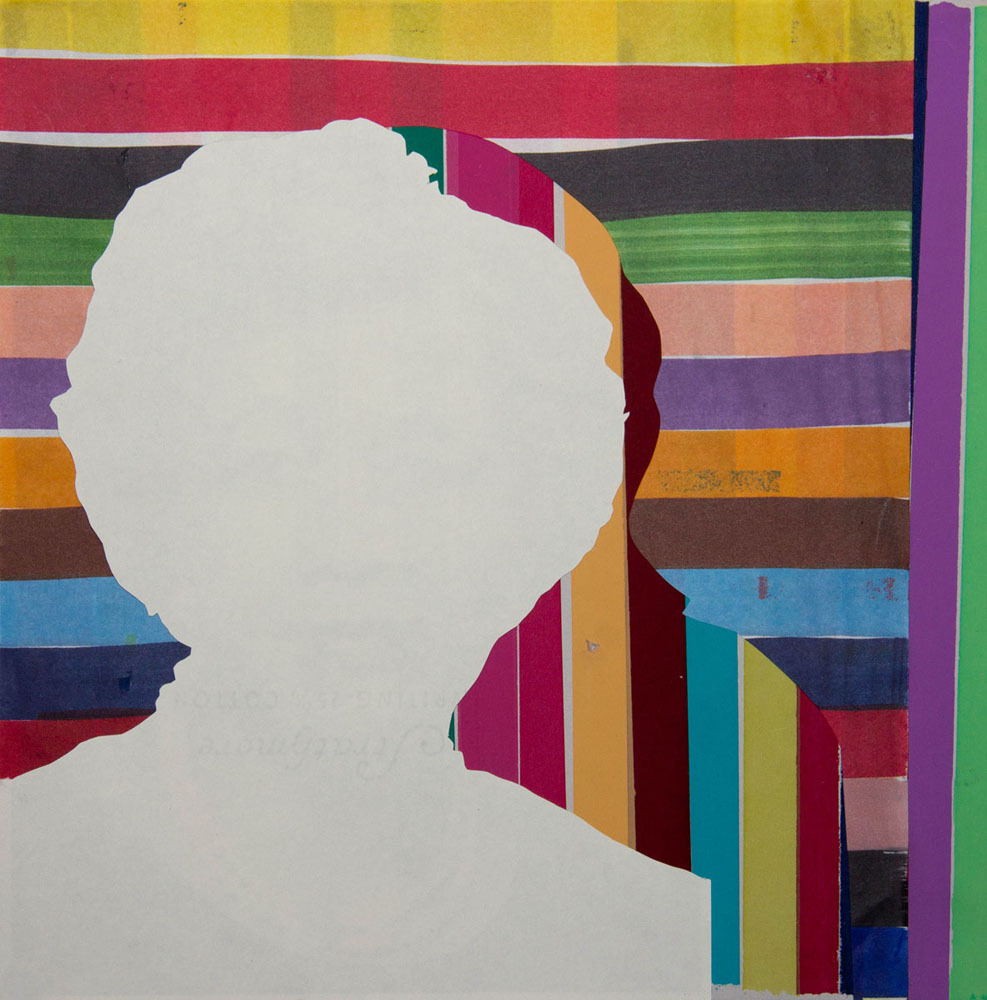

Dream Workers (Dorothy), Ink and collage on paper, 2014

Sayward: In the drawings, you use photocopied images of each person’s face, and place the paper facedown, so the viewer sees a sort of ghost image, not invisible but not fully visible.

Your use of (in)visibility makes me think of your text-based work. The viewer must slow down for the text to become language. To me this slowing relates to the laborious techniques you use. and the and especially because you like in making these you lay a walnut in ground and then. How did you arrive at hyper visibility and invisibility? In Dream Workers, for example, Martin Luther King and Fred Hampton are hyper visible figures, and yet they remain somewhat invisible in the ways American history is warped and rewritten. Is the relationship between invisible and visible something that surfaced while making the series?

I Feel (Brown), Colored Pencil and Walnut ink, 38"x50", 2017

Sayward: In the drawings, you use photocopied images of each person’s face, and place the paper face down, so the viewer sees a sort of ghost image, not invisible but not fully visible.

Your use of (in)visibility makes me think of your text-based work. The viewer must slow down for the text to become language. To me this slowing relates to the laborious techniques you use. How did you arrive at hyper visibility and invisibility? In Dream Workers, for example, Martin Luther King and Fred Hampton are hyper visible figures, and yet they remain somewhat invisible in the ways American history is warped and rewritten. Is the relationship between invisible and visible something that surfaced while making the series?

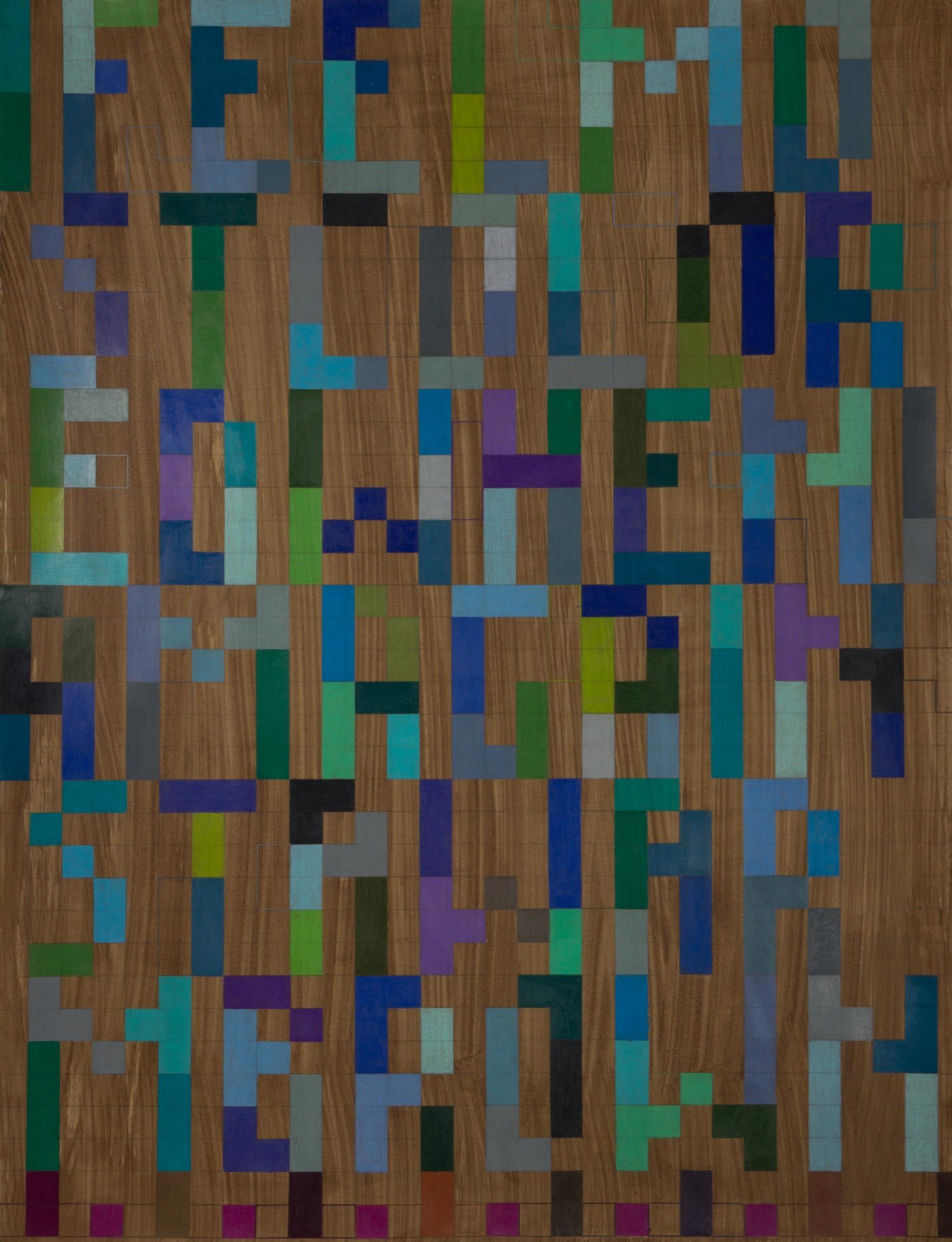

Mildred: It might have come out of there, but it wasn’t the language in my head at the time. I think another idea I was thinking about was hiding in plain sight: how people see what they see. And what it is they think they see? There are identity metaphors contained in that. With a lot of my work, there’s a way of understanding it from far away, but then as you come closer, and what it is you think you knew falls away a bit, and you have to understand it a different way. I think that's true for these text pieces. It’s also true for the pixelated figures because they don’t resolve. You want to get closer to them to see them better, but you lose what you're seeing as you get closer. So, you have to deal with like the particularity: you’re dealing with a particular shape or particular things. Not the picture you thought you understood or not the thing you thought you understood before you got close, so you have to form your own relationship. Your own physical movement, what you bring to it, how close you get, how far you get is going to affect what it is that you understand and what you take away.

The text-based drawings are 38 by 50 inches. A lot of the work has ended up that size because the size feels good to me in terms of how you confront it with your own body. The size just fits most people's torso in a particular way that you're sort of confronting it like a body. Thinking about the positioning of the viewer, how the drawing fills the frame of your own being, has started to become more important to me. These figurative works and these illegible text-based works deal with different kinds of legibility.

Sayward: You often use walnut ink in your work. Will you tell us the story of the walnut ink?

Mildred: I think it might have even been from Andrew Raftery that I first heard about walnut ink. One day I was at a birthday party in the Bronx at a park and these nuts kept falling all around me. I recognized them as black walnuts and collected a bunch, brought them home to Brooklyn and made my first batch of ink.

Sayward: So, they fell from the sky.

Mildred: They fell from the sky. And then I had a friend who worked at this place called the Wyckoff Farmhouse, which is a historic house museum and garden in Brooklyn. There was a black walnut tree there. I knew what they were then, and I got some there. Once I knew and saw them, it changed the way I looked at the world. My sister and I would gather nuts from a tree until her neighbor made her cut it down. She felt bad so then we drove around her neighbors in New Jersey to all these other places where they were cutting down walnut trees and collected nuts.

Sayward: Why were they cutting them down?

Mildred: People don’t like them because the tannins kill other plants, and the nuts stain the ground. They are trees that mark their territory, which I think is fascinating. I really like the process of making the ink. This happens to me: I become interested in something, and then I figure out something to do with it. Now, I just keep finding walnuts. I was walking in Prospect Park, and I had no idea they had black walnut trees there but I saw the nut on the ground. Then in Burlington, VT, I moved to a new neighborhood and there was a bunch of them. On my way to work I would collect them in a box and make walnut ink in my office between classes. You soak them in water and then boil them. It doesn't matter if they've been eaten, doesn't matter if they're green, or if they're dried out. The color of the ink depends on how much you boil it down. I like the color; it’s like brown skin. It's like wood.

Sayward: You get interested in something, you make it, and then you find something to do with it. This is an image of the white line woodcuts you’re working on now. You mentioned that you found squares of paper you had made awhile back and decided to use them for these prints. The block, too, was something you already had around. What is a white line woodcut?

White Line Woodcut, 2023

Mildred: White line woodcut is the Lazy American cousin of the Japanese woodblock. It’s also related to reduction wood blocks too, lazy reduction wood blocks. The reason it's called white line is because you the cut line prints white. In this process, I am printing with watercolor, so I hand color each shape in the block. To make these prints, I will color in one or two stripes, flip the paper onto the block, print it with a bone folder, flip it back, color a few more stripes, put it down and print. There is a lot of labor. It’s slow and meditative. My goal is to make 100 prints, but they're all from the same block.

Sayward: The block is bigger than the piece of paper you print on, so you can move the papers to different areas of the block, making different compositions.

Mildred: This process is relational, like my other work. I’m making decisions about color.

Sayward: The prints, while separate sheets, are interconnected because they all come from one block.

Mildred: How many ways can I envision the same space? I can make the prints loose or tight. I think that one of the reasons I took to printmaking is because it has constraints within the process. Having some of the decisions made frees me to make a lot of decisions within that structure. I feel like I can make tons of decisions and I can invent a lot within that constraint. But if I have to make every single decision, I get bogged down. The parameter feels more useful to me, and I can invent within that.

Sayward: A lack of structure, perhaps, can leave one awash without pointed dreams.

Mildred: People think anarchy means a complete lack of rules. I think anarchy requires more discipline than any other structure, more discipline.

Sayward: Yes, it makes me think, if we, for example, removed all the road signs and traffic laws, we'd all have to be hyper-vigilant of each other.

Mildred: You'd have to be aware, pay attention, you'd have to be responsive. You'd have to care.

Sayward: What might happen when you make something outdoors here?

Mildred: My idea is to make these little structures that move between image and text, thinking about symbolic imagery. It’s in the test phase. I’ve been walking around the grounds and will return home and keep thinking about materials that make sense and both for durability and also for outdoor resonance of some kind. I'm excited to do it.

Emily: Where do you think your impulse to make comes from?

Mildred: I don't know. Maybe my mom: she was a seamstress. She came to this country and worked in a factory. I didn't formally learn how to sew, but I learned by watching. I always saw a lot of making in different ways. My mom always made clothes for us. There was like a neighbor mentor woman, Teresa, who taught me and my sister to knit. My first knitting project was super ambitious! We made these 80s- style sweaters with color work. Both my sister and I both made the same sweater. I think I just always liked making things. I did a lot of beading when I was a teenager with my friends. I never really planned to be an artist. I just kind of kept making things and then it turned out that I kept being an artist. There was never any vision of becoming an artist.

Sayward: In college did you want to study art?

Mildred: I went to a science high school, and I took an AP class called medical illustration. So, when I went to college, I sent some drawings, and I think that's probably why the art teacher made a beeline to me and said, “Take art classes.” I do just feel like I just keep making things and collecting things.

Sayward: Something I find so wonderful, inspiring, and refreshing about your work is the beautifully clear material meanings that hold hands beautifully with big ideas and important histories vital to survival. Questions of how we make and live in a world that isn't racist and sexist and hateful. I also love that it’s evident that you make things out of the joy of being a maker and allowing yourself to make for making’s sake.

Mildred: The white line woodcuts are called What is to Be Built. It's a reset project in a way. It’s a thinking-through process. I'm thinking, I'm making, and then I can sort through the evidence. Thinking and rethinking and imagining